Visit Uncrate for the full post.

Visit Uncrate for the full post.

The good, the bad, and the meh.

Nothing President Donald Trump says about trade makes sense, so you have to look at the actual policy.

That’s especially true if you, like me, are broadly sympathetic to the view that the pre-Trump bipartisan trade policy consensus really had veered off course. And looking this morning at the text of the apparent deal to rework NAFTA — including a rebrand of the agreement as USMCA (a.k.a. the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement) — it seems like Trump has made the deal better in some ways and worse in others, and most of all has actually not changed the underlying structural flaws in the US approach to trade policy.

The good, the bad, and the meh

A lot of the US-Canada wrangling was about the technical details of dispute-resolution mechanisms, which I don’t think is very interesting in this context and where, at the end of the day, Canada overwhelmingly got its way and nothing is changing.

So we’re left with three big buckets of change.

The good: cars. The new deal both raises the share of North American auto parts that need to be in a car to qualify as NAFTA-compliant and also basically imposes higher minimum wage rules on Mexican auto factories. This is good for American autoworkers and probably good for Mexican autoworkers, and the downside is cars will be more expensive. But expensive cars are good! Obviously Trump is not much of an urbanist, but I am — and at the end of the day finding ways to discourage car ownership that help rather than hurt US autoworkers is a good idea.

The bad: copyright. As has become typical for American trade deals, one big thing we did was strong-arm our trade partners into adopting America’s super-long copyright term rules. This is good news for you if you happen to own the copyright to, say, Batman. But it’s bad public policy. And one of the worst things the US does is use international trade negotiations to spread our bad domestic copyright policy to foreign countries.

The meh: dairy. After all the screaming and yelling about Canadian dairy tariffs, we got Canada to make concessions on allowing imported American milk that are slightly bigger than the concessions they made in the Trans-Pacific Partnership. This is a nice small win for US dairy farmers and Canadians who consume dairy products. But that’s the weird thing about it: This is a concession the US “won” in the talks, but the winners are overwhelmingly Canadians. We are just saving them from their own dysfunctional dairy policy. Most Americans won’t be impacted at all, and if we are it will take the form of higher dairy prices.

Last, emphasizing Trump’s taste for theater, they are renaming the agreement so he can spin this set of relatively small modifications as him getting rid of NAFTA. They want to call it USMCA now, which is unpronounceable. I would suggest USMECA, which not only is a word you can say but would (like NAFTA) sound pretty similar in both English, Spanish, and French.

The problem with trade

What didn’t happen here was any change to the flawed way American thinks about trade policy.

The way trade is done in the United States right now is the United States Trade Representative’s office sits down with a bunch of representatives of powerful American interest groups and asks them what they would like to see in an international agreement. Then we go out and try to score those wins — wins that often are only tangentially related to trade policy. Any agreement done in this way is inevitably a mixed bag, and I think the critics tend to overstate their harms.

But it’s a backward way of thinking about what we want from trade policy.

What we ought to do is look through the other lens of the telescope. What are the big cost-centers for American citizens, and how can international economic integration make them less burdensome? Creating speedy pathways for foreign medical professionals to work here — or for medical work to be outsourced — should be a no-brainer. Opening up hyper-concentrated domestic industries like aviation to more foreign competition also belongs on the list.

The Canadians, in this sense, actually got the best deal out of this. Possibly by accident, they were “forced to” modify a bad domestic policy driven by an anti-competitive domestic interest group.

This is an abbreviated web version of The Weeds newsletter, a limited-run newsletter through Election Day, that dissects what’s really at stake in the 2018 midterms. Sign up to get the full Weeds newsletter from Matt Yglesias, plus more charts, tweets, and email-only content.

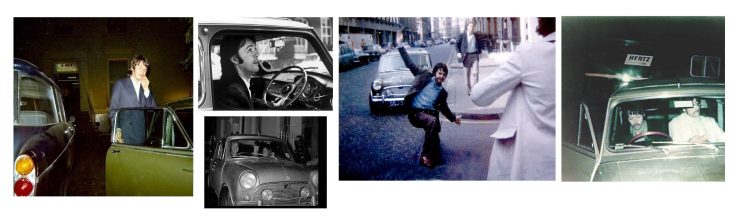

Sir Paul McCartney’s Mini Cooper S Is For Sale

It isn’t every day you get the chance to buy Sir Paul McCartney’s original Mini Cooper S.

The Harold Radford & Co Mini Cooper S

Radford was famous for impeccable coachbuilt Bentleys, typically for country gentlemen, in either shooting brake or estate wagon configuration with acres of walnut, leather, and plush carpeting.

It caused quite the stir when the company unveiled their bespoke Minis at the 1963 London Motor Show at Earls Court, overshadowing many far more costly vehicles, and it wasn’t long before the likes of Peter Sellers, Steve McQueen, and James Garner would order their own.

The Minis modified by Harold Radford & Co were fitted with a Webasto sliding sunroof, Aston Martin taillights, power windows, a wood-rimmed Moto-Lita three-spoke steering wheel, rich woodgrain interior accents, luxuriously upgraded bucket seats, a central armrest, Smiths instruments, custom wheels, and much, much more.

Each Radford Mini was created using the now legendary Mini Cooper S as a starting point, so the cars had ample performance capabilities to accompany their new luxurious refinements. Celebrities and those from the wealthier classes of society who found the original Mini a little too unrefined for their tastes generally loved the Radford version, and they sold in much higher numbers than any previous Radford creation.

The surviving Radford Minis almost all have their own fascinating stories, and they now change hands for significant sums of money – even the ones that weren’t owned by Beatles.

Sir Paul McCartney’s Radford Mini Cooper S

As you might expect, McCartney didn’t own just any Mini. Paul and each of his three bandmates owned specially ordered examples of the Harold Radford Mini Cooper S.

We previously featured Ringo Starr’s Mini, George Harrison’s belongs to his wife, and John Lennon’s disappeared years ago, and has since become a bit of an automotive mystery.

It was the Beatles’ famous manager Brian Epstein who would order the four cars for the four musicians in 1965. It’s impossible to calculate just how much this extraordinary exposure benefitted both Morris Motors (the Mini’s manufacturer) and Harold Radford & Co, but it doubtless played a large role in cementing the Mini as a pop culture icon in Britain and around the world.

After being sold on by McCartney the Mini ended up spending decades living in the Hollywood Hills under the care of Bill Victor, it was later sold to Michael Fisher in Miami, who had the car carefully restored back to original specification.

For the first time in almost 20 years the McCartney Mini is now coming up for sale – considering the fact that the Harrison Mini is still in family ownership, the Lennon Mini has vanished, and that the Starr Mini only sold recently, it’s possible that this is a once in a decade opportunity for collectors to get their hands on one of the most famous and beloved small cars in history.

If you’d like to read more about the car or register to bid you can click here to visit the listing on Worldwide Auctioneers. There’s currently no price estimate, and there’s also no reserve.

The post Sir Paul McCartney’s Mini Cooper S Is For Sale appeared first on Silodrome.

Google is tracking you, even if you turn off tracking:

Google says that will prevent the company from remembering where you've been. Google's support page on the subject states: "You can turn off Location History at any time. With Location History off, the places you go are no longer stored."

That isn't true. Even with Location History paused, some Google apps automatically store time-stamped location data without asking.

For example, Google stores a snapshot of where you are when you merely open its Maps app. Automatic daily weather updates on Android phones pinpoint roughly where you are. And some searches that have nothing to do with location, like "chocolate chip cookies," or "kids science kits," pinpoint your precise latitude and longitude - accurate to the square foot - and save it to your Google account.

On the one hand, this isn't surprising to technologists. Lots of applications use location data. On the other hand, it's very surprising -- and counterintuitive -- to everyone else. And that's why this is a problem.

I don't think we should pick on Google too much, though. Google is a symptom of the bigger problem: surveillance capitalism in general. As long as surveillance is the business model of the Internet, things like this are inevitable.

BoingBoing story.

Good commentary.

A Level 4 drought classification indicates conditions are extremely dry and that the water supply won't meet economic or environmental needs.

I have been talking about Pinterest as a disinformation platform for a long time, so this article on QAnon memes on Pinterest is not surprising at all:

Many of those users also pinned QAnon memes. The net effect is a community of middle-aged women, some with hundreds of followers, pinning style tips and parfait recipes alongside QAnon-inspired photoshops of Clinton aide John Podesta drinking a child’s blood. The Pinterest page for a San Francisco-based jewelry maker sells QAnon earrings alongside “best dad in the galaxy” money clips.

Pinterest’s algorithm automatically suggests tags with “ideas you might love,” based on the board currently being viewed. In a timely clash of Trumpist language and Pinterest-style relatable content, board that hosts the Podesta photoshop suggests viewers check out tags for “fake news” and “so true.”

The story is a bit more complex than that, of course. It’s not clear to me that the users noted here are not spammers (as we’ll see below). It’s quite possible many of these accounts are people mixing memes and merchandise as a marketing amplification strategy. We don’t know anything about real reach, either. There are no good numbers on this.

But the threat is real, because Pinterest’s recommendation engine is particularly prone to sucking users down conspiracy holes. Why? As far as I can tell, it’s a couple of things. The first problem is that Pinterest’s business model is in providing very niche and personalized content. It’s algorithm is designed to recognize stuff at the level of “I like pictures of salad in canning jars”, and as Zeynep Tufekci has demonstrated with YouTube, engines of personalization are also engines of radicalization.

But it’s more than that: it’s how it goes about recommendation. The worst piece of this, from a vulnerability perspective, is that it uses “boards” as a way to build its model of related things to push to you, and that spammers have developed ways to game these boards that both amplify radicalizing material and and provide a model for other bad actors to emulate.

How Spammers Use Pinterest Boards as Chumbuckets

The best explanation of how this works comes from Amy Collier at Middlebury, whose post on Pinterest radicalization earlier this year is a must-read for those new to the issue. Drawing on earlier work on Pinterest manipulation, Collier walks through the almost assuredly fake account of Sandra Whyte, a user who uses boards with extreme political material to catch the attention of users. Here’s her “American Politics” board:

These pins flow to other users’ home pages with no context, which is why the political incoherence of the board as a whole is not a problem for the user. People are more likely to see the pins through the feed than the board as a whole.

Once other users like that material, they are more likely to see links to TeeSpring T-shirts this user is likely selling:

The T-Shirts are print-on-demand through a third-party service, so hastily designed that the description can’t even be bothered to spell “Mother” right.

So two things happen here. When Moms like QAnon content, they get t-shirts, which provides the incentive for spammers to continue to make these boards capitalizing on inflammatory content. Interestingly, when Moms like the T-shirts, they get QAnon content. Fun, right?

How Pinterest’s Aggressive Recommendation Engine Makes This Worse

About a year ago I wrote an article on how Pinterest’s recommendation engine makes this situation far worse. I showed how after just 14 minutes of browsing, a new user with some questions about vaccines could move from pins on “How to Make the Perfect Egg” to something out of the Infowarverse:

What was remarkable about this process was that we got from point A to B by only pinning two pins on a board called vaccination.

I sped up the 14 minute process into a two and a half minute explanatory video. I urge you to watch it, because no matter how cynical you are it will shock you.

I haven’t repeated this experiment since then, so I’m unable to comment on whether Pinterest has mitigated this in the past year. It’s something we should be asking them, however.

I should note as well that the UI-driven decontextualization that drove Facebook’s news crisis is actually worse here. Looking at a board, I have no idea why I am seeing these various bits of information at all, or any indication where they come from.

Facebook minimized provenance in the UI to disastrous results. Pinterest has completely stripped it. What could go wrong?

Pinterest Is a Major Platform and It’s Time to Talk About It That Way

Pinterest has only 175 million users, but 75 million of those users are in the United States. We can assume a number of spam accounts pad that number, but even accounting for that, this is still a major platform that may be reaching up to a fifth of the U. S. population.

So why don’t we talk about it? My guess is that its perceived as a woman’s platform, which means the legions of men in tech reporting ignore it. And the Silicon Valley philosopher-king class doesn’t bring it up either. It just sounds a bit girly, you know? Housewife-ish.

This then filters down to the general public. When I’ve talked about Pinterest’s vulnerability to disinformation, the most common response is to assume I am joking. Pinterest? Balsamic lamb chops and state-sponsored disinfo? White supremacy and summer spritzers?

Yup, I say.

I don’t know how compromised Pinterest is at this point. But everything I’ve seen indicates its structure makes it uniquely vulnerable to manipulation. I’d beg journalists to start including it in their beat, and researchers to throw more resources into its study.